|

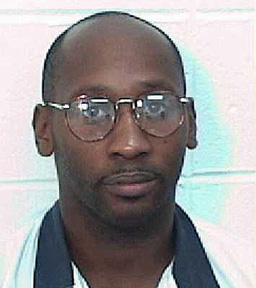

| (Erik S. Lesser / AFP-Getty Images / September 21, 2011) |

You may have noticed the crowd gathered outside of the prison where Troy Davis was murdered. Supporters all. African Americans almost completely. A very few white faces sprinkled in the crowd. How long before the white left wakes up and realizes that vast majority of white Americans are, in fact, white Amerikans first. I don't discount the voices of some white folks, even conservative Bob Barr, amongst the famous calling for a reprieve. You know, for the most part, they've moved on. They have dried their tears and taken up more "important" matters.

And Troy Davis...he is dead...just like so many before him...and so many more to come.

Some day the bastards will pay.

The first below comes from BeatKnowledge and the second from The Atlantic.

Troy Davis: strange fruit in 2011

This song, first recorded in 1939, still resonates today, the morning after the legal lynching of Tro’t think it could happen – many thought the (black) President would intervene, or that that the Supreme Court would listen to the numerous human rights organisations that were calling r clemency. But the truth is that systemic racism and white supremacy are still very much alive, and the racist far-right is in the mood for re-asserting its authority.

Forward against the racist system, by any means necessary.

Southern trees bear a strange fruit

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root

Black body swinging in the Southern breeze

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.

Pastoral scene of the gallant South

The bulging eyes and the twisted mouth

Scent of magnolia sweet and fresh

And the sudden smell of burning flesh

Here is a fruit for the crows to pluck

For the rain to gather

For the wind to suck

For the sun to rot

For a tree to drop

Here is a strange and bitter crop

=================================================================

The Night They Killed Troy Davis

JACKSON, Georgia -- The Georgia Diagnostic and Classification Prison sits a quarter mile off Interstate 75 in Jackson, just outside the commuter suburbs of Atlanta. The technical name for the place obscures its most notorious function: it houses the death chamber for the state's executions. Last night, for more than seven hours, hundreds of people prayed, chanted, sang, hoped and shouted in front of that building in a vain effort to prevent the state of Georgia from extinguishing the life of Troy Davis.

A trickle of people began showing up outside the prison in the late afternoon. By 5 p.m. they had grown to about 200 and been cordoned off by police tape in front of a truck stop across from the prison. A knot of organizers from Amnesty International unfurled a huge banner saying "Free Troy Davis" and another set of activists held a sign saying we had returned to the days of the Scottsboro Nine. A principal came out with several of his elementary school students and a busload of students poured in from Spelman and Morehouse Colleges. But the largest group was from Al Sharpton's National Action Network -- at least thirty of whom had driven up from Savannah, where the murder of Mark McPhail took place. They set about coordinating the chants, moving people with signs to the forefront so that passersby could see exactly what we were protesting and generally keeping the protests going.

Initially the police outside the prison were unfazed by our presence, relaxed enough to be polite. But that changed as we drew closer to the scheduled hour of the execution. At about 6 p.m., local law enforcement, sheriffs, SWAT teams and state troopers began putting on riot gear. Over the course of the next hour they moved closer and closer to the protesters with their batons in hand. For their part they may have hoped that their show of force would prevent things from getting out of control but the reality is that it appeared that they wanted to instigate violence. It was impossible not to realize that from their perspective, we were praying for a man who had gunned down their fellow officer.

By 6:30 the crowd numbered at least 500 people. We spilled past the tape and onto the grassy barrier between the truck stop and Prison Boulevard where the facility is located. Trucks pulled in and out of the station began honking their horn in support of Troy Davis's cause.

But what was most surprising and disturbing is that the group was more than 90% black. For all the discussion about the implications of the death penalty for the country at large this broke down, as always, to an issue of race and black people would have to do the heavy lifting if any change were going to occur. The racial balance skewed so heavily that when a young white couple sat down on the grass next to me I asked them what organization they were with. The woman reply hit me hard: "We're not with an organization. I know Troy Davis -- my brother is on death row with him."

By 7 p.m. people nearly everyone there was crying or praying or both, imploring God to save Troy Davis's soul if he would not save his life. In the midst of this I realized that there were no counter-protests. Later I learned there were a few. But still I saw no crowds gathered to voice their support for what was happening inside that prison. This was a small grace but it was also possibly because few believed that Davis' fate was ever in doubt. And they had no reason to.

Georgia's criminal justice system is a microcosm for the kind of racial disparities that plague the entire country. Blacks are 30.5% of the state's population but make up 61% of Georgia's prisoners. A few years back the state legislature, in the name of getting tough on crime, passed a bill that created draconian penalties and allowed juveniles to be charged as adults for a wide array of crimes, including simple robbery, which would normally be handled by a juvenile court. The legislation was so poorly written that in the state if a 14 year old and a 35 year old rob a liquor store together, the teenager can - and in some instances has -- received a sentence longer than that of the adult. It can go without saying that these laws have disproportionately impacted black youth.

Both the state legislature and the governorship are firmly in the hands of the GOP and, though the newly elected Nathan Deal remains the subject of a federal corruption probe, no Democrat has stood a chance of becoming governor since Roy Barnes was turned out of office for opposing the Confederate flag nearly a decade ago. This is Georgia in the 21st century, the state that claimed, despite recantations, police coercion, contrary evidence and the lack of physical evidence, that it was certain beyond a reasonable doubt that Troy Davis was responsible for the death of Mark McPhail and that he should die for it.

The sobs of the mourning crowd were punctured by shouts when we heard that the Supreme Court had stepped in to review the case. The reality is that this crowd, predominantly African American, many battle-wearied activists, still believed that this execution simply could not happen. For hours, their energy and commitment unflagging, people beat drums, held candles and sang civil rights songs. And here lies the paradox: even as people most intimately aware of the failings of this country, so many of us subscribed to a faith that justice would prevail that when we received word of the court's refusal to grant a stay the reaction was stunned disbelief.

The feeling, as I stood in front of the truck stop in the middle of the night, was that we were witness to a great evil -- not solely the taking of what may well have been an innocent life, but also in the false certainty that sought to sell this killing as justice. When word came at 11:08 p.m. that Troy Davis was no more, women began wailing; several of them fell to the ground heaving inconsolably. A few men offered stumbling, meandering prayers that some good might come of this, that it would inspire some greater reckoning with the arbitrary, corrupted realities of capital punishment in this country.

And I, at that point, thought about my father, a native of Hazlehurst, Georgia who had abandoned his home state for New York in 1941. He lived the remainder of his life there, firm in his belief that a black man's life was seen as worthless in Georgia. I grew up hearing the stories of the sadistic violence that was commonplace there, about a black women he'd known growing up who was raped and tortured by white men who went unpunished. I moved to Georgia in 2001, secure in my belief that the place had changed, that our efforts had yielded success and the stories my father told me were now consigned to the horror closets of history.

But last night, progress, hopes and a black presidency be damned, the state of Georgia had the last word. And they were determined to prove the old man right.

No comments:

Post a Comment